Tox Report 70. Feminism's blue future

Did the left lose feminism? (No, but maybe feminism wasn't its to lose)

Greetings Tox Nation! It’s been a very busy week, and there nearly wasn’t a newsletter for you. But then I remembered this feature has been languishing in my drafts, so you get to read it. It was originally written almost 18 months ago, and though I’ve updated it lightly, a lot has changed since then. But since we’re on the cusp of one of its subjects possibly becoming the new opposition leader, it felt like a good moment to bring it out of the closet.

Until a few years ago, if you’d asked me whether it was possible to be a feminist and right wing, I’d probably have laughed derisively at you. Not only was there no such thing as a conservative feminist, but feminism was in opposition to everything conservatism stood for. It was a simple oxymoron.

Maybe I’d have given a different answer if I’d lived through a different era. Suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst stood as a Conservative candidate after women won the vote. Militant activist Mary Sophia Allen even went from smashing windows for women’s rights, to supporting the British Union of Fascists.

But I grew up under the reign of Thatcher, who considered women’s rights a done deal. With her prim pussy bows and insistence on serving shepherds pie to the cabinet, Thatcher played the traditional women even while she was running the country. She called feminists “strident” and referred to them derisively as “women’s libbers”.

The animosity was mutual. “Mrs Thatcher is a woman, but she certainly isn’t a sister,” tutted Eileen Fairweather, editor of the feminist magazine Spare Rib. Feminism, after all, was a radical movement: patriarchy was the status quo, and feminism existed to overturn it. Thatcher’s hostility to economic redistribution and unabashed militarism put her firmly outside the women’s movement.

This opposition between conservatives and feminists went further than optics. Every major piece of legislation advancing women’s rights since World War 2 has happened under a Labour government: the 1967 Abortion Act, the 1975 Sex Discrimination Act, the 2010 Equality Act.

The Conservative riposte to this was that Labour to this day has never had a female leader (although it does at least now have a female chancellor, and the first in the history of the British government). Meanwhile the Tories have had three — after Thatcher, Theresa May and Liz Truss — all have served as PM (albeit briefly in Truss’s case). And unlike Thatcher, both May and Truss were keen to associate themselves with feminism.

May was photographed beaming proudly in a “this is what a feminist looks like” T-shirt. Truss called herself a “Destiny’s Child feminist” — meaning, she explained, that women should be “independent” and not treated as “victims who need special help and special treatment”.

This suggested a thaw in relations between conservatism and feminism. Even so, May and Truss had to share their party with figures like Phillip Davies, who claimed the justice system was biassed against men, and Dominic Raab, who called feminists “obnoxious bigots”. And the left-wing majority of the feminist movement treated both women with outright suspicion.

But something strange happened in the last few years. During the previous parliament, it was on the Tory benches, not the Labour ones, that you’d find the staunchest defenders of Labour’s Equality Act. A bracing political strand calling itself “reactionary feminism” now argues that women have been failed by liberalism, and might be happier in the old institutions of marriage and stay-at-home motherhood. Is it possible that the future of feminism belongs to the right?

If it does, it probably looks a lot like Kemi Badenoch. Badenoch, 44, served as secretary of state for business and trade as well as minister for women and equalities. If she can beat Robert Jenrick in the current leadership election, she will become the Conservative’s fourth female leader.

There’s still a residual attitude that a black woman like Badenoch ought to belong to the left — that if she’s espousing conservative views, then she must be (in the patronising words of one critic) a “white-man parrot”. Badenoch even joked about this in her maiden speech. “I am often inexplicably confused with a member of the Labour party,” she said. “I cannot think why.”

Badenoch is most definitely a Tory. She’s a believer in free markets and free trade, and a vocal opponent of identity politics. (As a Briton of Nigerian descent, she can point to her own success to argue against the idea that the UK is fundamentally racist.) But she’s also a feminist, and has frequently taken the lead in defending the Equality Act (albeit a feminist who, during her leadership campaign, declared that maternity leave is “excessive”).

Sources close to her say that her take on sexual equality is pragmatic, and she doesn’t see women’s rights as the province of any specific political movement. She’s animated by real-world experiences, both her own and her constituents’. For Thatcher, feminism was a bogey to be repudiated; for Badenoch, it’s just common sense.

Miriam Cates, who was the Conservative MP for Penistone and Stocksbridge until this year’s general election, has a similarly robust take. “I’ve never thought of myself as not a feminist,” she says, blonde hair bouncing as she speaks to me over Zoom. “I’m absolutely convinced that women should have equal rights under the law and equal opportunities.”

But Cates also distinguishes herself from what she calls “the more extreme economic aspects of feminism”. For one thing, she thinks that feminism has historically been too fixated on “pushing women into having careers”: she thinks the state should invest at least as much in supporting stay-at-home mothers as in subsidising nurseries.

A reminder that my book Toxic is now available in paperback! It’s the story of how the internet drove everyone crazy in the noughties, told through the lives of nine celebrity women and the battle to control their own images. Helen Lewis called it “a Molotov cocktail hurled at the feet of celebrity culture”, and Paris Hilton liked it so much she bought the TV rights. Click the button below to buy from Amazon, or head to your bookseller of choice.

And if you’ve read and enjoyed Toxic, please use those links to leave a review! It really does make a difference, and I appreciate everyone who’s done this already.

For Cates, it’s a foundational truth that men and women are different — not just in the obvious physical ways, but in their interests, aptitudes and psychology. And while she accepts that there’s plenty of variation within men and women (she herself was a science teacher, despite that being a stereotypically masculine interest), she says the trends are undeniable. “I look at the evidence. Of course girls like playing with dolls more than boys.”

She calls herself a “reality feminist”. “I’ve always thought that one mistake that feminists did make in the eighties and nineties was to say that men and women are the same,” she says. “And possibly, that’s made it a lot harder to defend ourselves against the gender identity movement. We’ve had to roll back a bit and say, no, we’re actually different.”

The gender identity movement started to make legislative in-roads in the middle of the last decade with a push to end the medicalised process of getting a gender recognition certificate, and allow individuals to self-identify their legal sex. It was an aim supported by many people out of a liberal concern for trans people’s wellbeing. But, it’s subsequently been argued, it comes with unintended consequences for women’s rights.

This is no mere theoretical conflict. In January last year, in Scotland, a male double rapist identifying as a trans woman under the name Isla Bryson was sent to a female jail. It wasn’t the first such instance (in 2018, a convicted male paedophile going by the name Karen White sexually assaulted female inmates while housed in a women’s prison), but the timing made it especially contentious.

Two months previously, the SNP government at Holyrood had pushed through the Gender Recognition Reform Act (GRR), which effectively introduced self-identification. That made Bryson a particular embarrassment to then-first minister Nicola Sturgeon, who had personally backed the new law and accused those criticising it of bigotry.

In January, the Westminster government blocked the GRR under section 35 of the Scotland Act, citing a conflict with the Equality Act. It was a move widely understood to have been orchestrated by Badenoch. Sturgeon, whose leadership of the SNP was already vulnerable on several fronts, resigned within weeks of the Bryson story breaking.

On the face of it, this fitted precisely with the “left-wing overreach” theory that Cates endorses. Sturgeon is a social democrat and a self-proclaimed “proud feminist”, who argued herself in a corner where it was impossible for her to say a convicted rapist was a man.

But there’s a problem with this theory. Although gender identity is often parcelled in with left-wing progressive values, until recently it was not a party political issue in the UK. As Labour leader, Jeremy Corbyn supported self-identification, but so did Theresa May, the prime minister at the time.

“A Tory government opened this can of worms in the first place,” says Judith Green, of the left-leaning campaign group Women’s Place. “It goes back to Maria Miller.” In 2016, Miller — the Conservative chair of the Women and Equalities Select Committee — fronted a report calling for the introduction of self-identification.

Yet somehow the Conservatives ended up holding the more robust position on women’s rights, while until close to the last election, Labour politicians consistently floundered when it comes to even saying what a woman is. Scottish Labour backed the GRR. The hashtag #labourlosingwomen intermittently trends on Twitter. Some female voters say it’s been enough to alienate them from Labour for good.

For the self-styled reactionary feminist writer Mary Harrington, “conservatism” isn’t enough. “I don't think there’s enough left to conserve, and too much of conservatism is just committed to conserving the liberalism of 20 years ago,” she tells me. She quotes the philosopher Nicolás Gómez Dávila: “the true reactionary is not a seeker after abolished pasts, but a hunter of sacred shades on the eternal hills.”

Others take an even more extreme position. Posie Parker, a populist campaigner against gender self-identification who’s been criticised for associating with the far right, describes herself as disillusioned with not merely the left but with feminism itself. “I think,” she says in one YouTube video, “in order to defend women’s rights, we’re gonna have to abandon feminism.”

When I speak to Julie Bindel, she’s in Newcastle covering the trial of David Boyd for the murder of seven-year-old Nikki Allen in 1992. Bindel, 60, has been campaigning against male violence since she was a teenager. As an out lesbian in Leeds, she was radicalised by the Yorkshire Ripper murders and the way misogyny blighted both the police investigation and the reporting.

She’s also robustly left-wing. “You don’t need to be a feminist to go bonkers about gender madness,” she says. Knowing women are female is a necessary condition for feminism, but not a sufficient one. “You can’t have a right-wing feminist.” For Bindel, feminism is necessarily radical, and she’s disturbed by women who call themselves feminists aligning with conservatism.

Cates’ “reality feminism”, for example, seems to entail a lot of things that might otherwise be called “anti-feminism”. A few weeks after I interview her, she gives a speech at the National Conservatism conference in which she blames “liberal individualism” for falling birthrates and argues that the state should encourage women to be stay-at-home mothers.

It’s a natalism that, for many, will sit uneasily with the project of women’s liberation. When I ask Cates if she thinks abortion rights could be reversed in the UK, she describes it as a “settled issue”, and points out that the Conservatives expanded abortion rights by allowing at-home medical terminations. Cates herself, though, opposed their introduction.

Sometimes reactionary feminism can sound a little like a counsel of despair. “I don’t really believe in patriarchy,” says Harrington. “I think patriarchy is actually an emergent property of men and women’s efforts to balance the competing interests of a sexually dimorphic species.” It’s a position that, taken at face value, suggests there’s little point in trying to change society.

But society does change. When the campaign for women’s suffrage began, it was resisted with extreme hostility and violence. A century later, we had a female prime minister. Sometimes a cause is powerful enough to unite women from across the political spectrum: it happened with votes for women, and it’s happened again with the resistance to gender identity. And today, as then, what happens to the movement after the victory is anyone’s guess.

Gimme, gimme more…

The Disney+ adaptation of Jilly Cooper’s Rivals comes out this week — I’ve watched all of it (and written about why Jilly Cooper is the balm the female libido needs after years of bed death seriousness) and it is the most fun I’ve had sitting down in, ooh, ages. (UnHerd, paywall/registration.)

And since I’m recommending TV: Ludwig is a delight. Warm, clever, perfectly paced murder mysteries. Treat yourself and watch the lot on iPlayer.

I’ve had this essay about “SAHM shame” open in my tabs for about a week, and still don’t know what to make of it. Is this a thing that happens? (Marie Claire.)

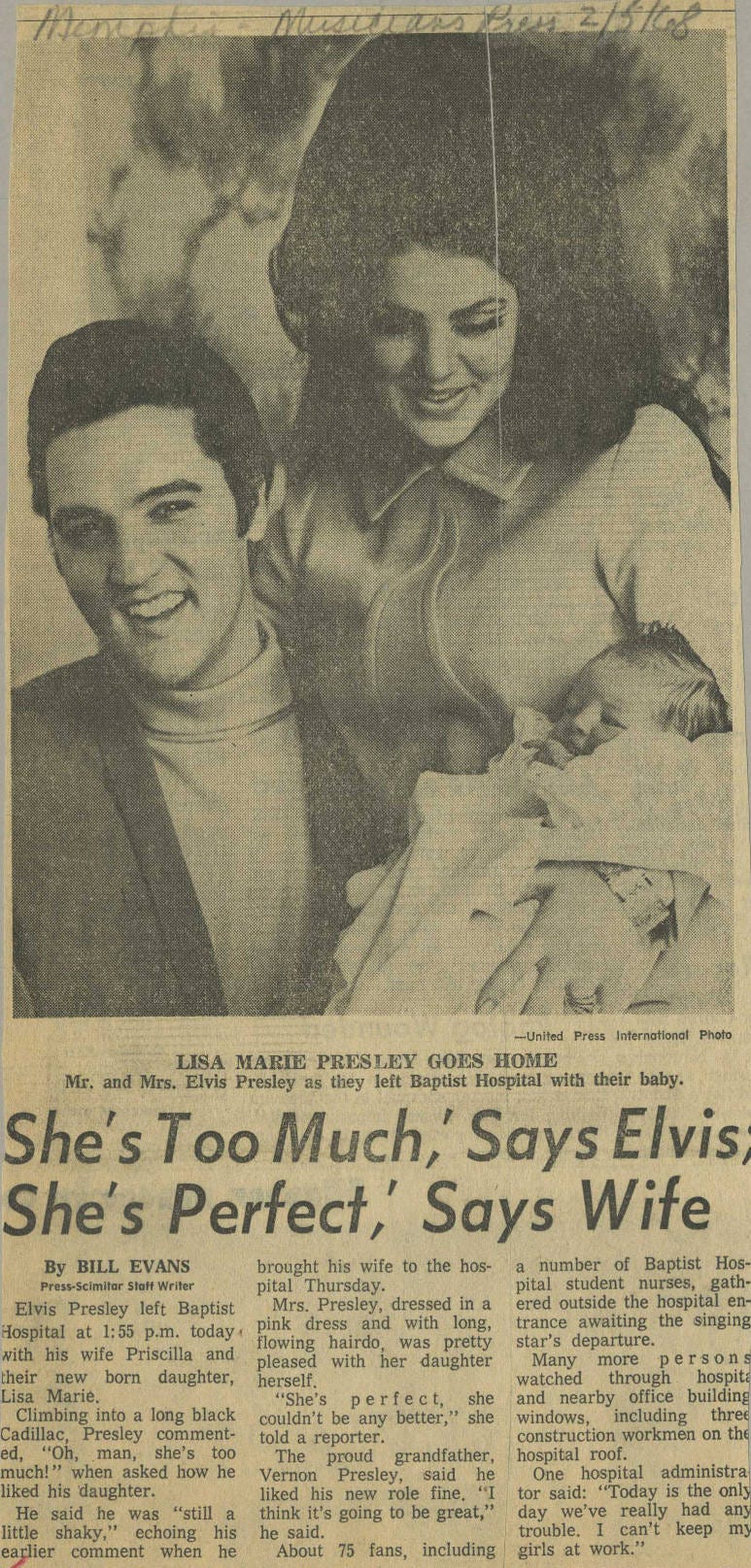

I also reviewed Lisa Marie Presley’s posthumous memoir. It’s one of the most fantastically sad books I’ve ever read, but there’s something genuinely touching about the way it’s been co-written by her and her daughter Riley Keough. (The Times, paywall/registration.)

I mean, look at her. Didn’t stand a chance:

It was in fact feminists who first floated the idea that women should be compensated for keeping a home and raising children in the 1970s and 80s. The slogan was, "Wages for housework." There have been many kinds of feminism, emerging at different historical moments, and feminism has most of all been a series of debates, proposals, and experiments.

I'm in agreement with Julie Bindel on this and totally at odds with the position of right wing populists. Working across the political divide is great when it works. However, seeing women, active in LWS, sticking up for racist thugs and cheering on the rioters who terrified totally innocent women, children and men, is beyond the pale. It reminds me of the old adage, 'if you lie down with dogs, you get fleas'.