11. The last gasp of the celebrity sex tape

Things change, and then you forget they were different

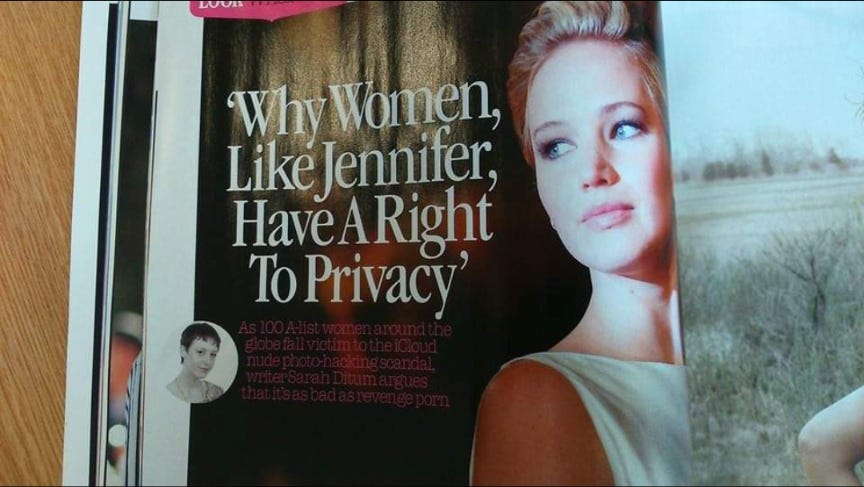

In September 2014, I got an email from an editor at Look magazine. Look had launched in 2007, following the then-successful Grazia model of mixing fashion and beauty with celebrity coverage for an aspirational readership of professional young women; it would close in 2018, but for me then, this was a big deal. I’d recently taken a job on a tech website after a stint of trying — and failing — to make freelancing properly happen, and any chance to push out of the “blogger” niche and into the world of print felt like it could be the break I was waiting for.

“We’re doing a piece on the nude pics and sex tape iCloud hacking scandal and I was wondering if you wanted to do a opinion piece for us — highlighting how it shouldn’t be a free for all and how it [is] not surprising these women have been shaken by it,” wrote the editor. (The incident in question was the leak known, grimly, as “the Fappening”.) You can tell how incredibly green I was, because I replied immediately saying I was available and not asking about the fee (now every inquiry gets a sob story about how painfully busy I am and a shameless statement of my rate).

But it’s not just my career that’s changed in the interim. In the commission, and in the copy I filed, you can see a shift taking place in the way the public thought about privacy. The copy I filed concluded:

The theft and distribution of these pictures is a form of revenge porn, only it’s not a bitter ex-boyfriend behind the abuse this time, but a twisted public that thinks famous women owe everyone access to their bodies. But what we do in our own homes and with our own phones isn’t anyone else’s business, and having your most personal moments published hurts, whoever you are. Whether you’re a celebrity or a civilian, you’ve got the right to a private life. That’s what this attack tried to take away from the women it targeted, and that’s why none of us can afford to let the hackers win.

This was a piece designed to catch a change in mood: some people think that hacked celebrity nudes are fair game but we (the magazine and its readers) know otherwise. To me now, this feels incredibly alien: not the position I took or the fact I was asked to write about it, but the fact that I was implicitly arguing against a position that said hacking, distributing and looking at private photos was absolutely fine.

About eighteen months earlier, in 2013, the Steubenville rape case in Ohio had ended in conviction for two high school football players. This would not, in pre-internet times, have been a global story. But in pre-internet times, it probably wouldn’t have been a story at all: this was a drunk girl at a party vs beloved jocks, “asking for it” vs “boys will be boys”. There would have been no evidence that couldn’t be ignored if it hadn’t been for the perpetrators making, and sharing, images of the attack.

Laurie Penny called Steubenville, memorably, “rape culture’s Abu Ghraib moment”. There’s truth in that. Rape is so often portrayed a private moment of confusion, a he-said she-said, and her words rarely have the standing of his. The Steubenville pictures showed rape as a social phenomenon: a collective activity between boys over the senseless body of a girl. They showed what rape looked like to a rapist.

The pictures only existed because the boys wanted to share their triumph, preserve it, celebrate their trophy fuck. They had to be seen to make sense of the crime, and to look at them was also to participate. Steubenville helped to create a collective understanding that the image is part of the abuse, that even if the image is not of an instance of violence, to look at someone who has not consented to be looked at this way is to commit a violation.

This was, incredible as it seems, something relatively new. In 2012, Gawker had published the Hulk Hogan sex tape — a tape which Hogan had said repeatedly had been taken without his knowledge or consent and that he did not wish to be made public. It was the last gasp of the celebrity sex tape in mainstream media.

Since the appearance of the Pamela Anderson and Tommy Lee one in 1998, they’d been a mainstay of internet culture through the noughties: some were stolen (Fred Durst), some released by one of the parties involved against the will of the other (Paris Hilton), some leaked by the person featured in the hope of advancing their profile (the wrestler Chyna).

Sometimes they weren’t celebrities at all: in 2010, Gawker published a video of a drunk young woman having sex (given her intoxication, probably being raped) in a bathroom stall. When the woman complained, the company’s lawyer emailed her saying the video was “completely newsworthy”, adding: “one’s actions can have unintended consequences.” The term “revenge porn”, which might have given the woman a framework for the injury done to her, had only started to tentatively appear in the mainstream the year before,1 and was still obscure.

There was, in other words, a grey area in the noughties which allowed any images of anyone arguably public or in a public place to be taken as potential fair game. That didn’t really change until social media and recording technology had developed to the point that everyone — whether they sought fame or not — understood that they were a potential victim, and at risk of being embarrassed on the internet. Hogan sued Gawker with the backing of billionaire Paypal-founder Peter Thiel, who used the case to exact revenge for Gawker outing him in 2007 — a story brilliantly told by Ryan Holiday in the book Conspiracy.

The shattering damages awarded to Hogan in 2016 finished off Gawker as a publisher,2 and meant that publishers in general would never be so cavalier again with sex tapes. And Holiday explains that part of the strategy Hogan’s team used to achieve that result was to select a jury that, based on mock trials they conducted, they believed would feel particularly keenly the intrusion and humiliation that Hogan had felt:

In those expensive mock juries, they had discovered that their case played exceedingly well to a very specific type of person. “It became very clear that the kind of jurors we wanted were overweight women. Most people can’t empathize with a sex tape, but overweight women are sensitive about their bodies and feel like they have been bullied on the internet. Men don’t have that problem. Attractive women don’t have that problem. They haven’t been body shamed,” Mr. A [the go-between who worked for Thiel] tells me proudly. Hypothetical Juror #3 might not have been a victim of revenge porn. She might not care about celebrity privacy. Hypothetical Juror #3 might not have known what it feels like to be Hulk Hogan, but she knows what it’s like to have an unflattering picture of herself on the internet. She knows what it feels like to be embarrassed or ashamed. Which is why they would choose her.

It’s an irony — but a very routine one — that something which primarily wounded women ended up being addressed in a case where a man was the victim. The case law of sex discrimination has advanced more often than not by finding cases where men were put at a disadvantage, even if the overall burden of unfairness tended to fall on women.

What’s interesting to me is that Hogan got his justice, and Thiel got his revenge, in part because their lawyers understood that women (a particular subgroup of women, in their reading) felt this hardest. “Everyone has the right to a private life,” I’d written in 2014, and reading it back now it seems so banal I can’t believe I got paid for it. But it needed saying. All through the noughties, it hadn’t been true.

Drop me an email or leave a comment if you’d like to — I’ve really enjoyed hearing your takes on the upskirt decade so far.

Gimme, gimme more…

Me for the Telegraph on the real battle of Spears vs Spears. It's not about the conservatorship now: it’s about whether any member of the family can survive Britney’s slow-burn project of revenge.

No one better to write about the end of the Cowell era than Tanya Gold. “He was his greatest product and his greatest success; his personal journey was the most successful in the entire genre and watching the promise of fame afflict his contestants was, entirely, the game. What would they hand over for our attention? Their dignity? Their privacy? Their sanity? Could Susan Boyle hack it? That was the question.”

I’d forgotten this story about Calvin Harris until it came up in the pub. Extremely relatable content.

I think this is the case, anyway — link decay makes tracking these things hard, but that 2009 Forbes article certainly has the tone of introducing a new concept to the world.

It relaunched this year, after the title was purchased by Bustle Digital Group, and it’s as boring as hell. Turns out that once you take out the aggro and snark to suit a 2020s sensibility, there really isn’t much left to enjoy about Gawker.