I was supposed to watch a revival of Stephen Frears’ The Grifters last week. I didn’t get to, because my train was an inexplicable 30 minutes late. So I watched Saltburn as a consolation — a film that I was quite interested in but not so interested that I wasn’t liable to miss it at the cinema and end up seeing it at home.

Which would have been a travesty, because Saltburn is gorgeous: full of lush, lovely scenery and sets which you will enjoy best when they’re able to ravish you at scale. And people: I’d be committing a grievous lie if I didn’t mention that one of the great and unexpected pleasures of Saltburn is Barry Keoghan’s extremely jacked body, which is on show for a phenomenal stretch of the run time. Truly, director Emerald Fennell is the Fellini of our time, by which I mean she has made a profession of getting people she fancies to run around beautiful places with their clothes off.

People get chippy about Fennell’s work — there is currently a heaving Saltburn class politics discourse. In the case of Fennell’s debut feature, 2020’s Promising Young Woman, people read (and embraced) the film a kind of #MeToo Dirty Weekend, then got mad at it for being the wrong kind of #MeToo Dirty Weekend: “Review after review claims Promising Young Woman is a feminist triumph. Where exactly are they locating that triumph? History isn’t made by well behaved dead women,” grouched critic Ayesha A Siddiqi in a Substack post that went viral, and which even offered an alternative plot she would have found more agreeable.

Siddiqi objected to the fact that the protagonist of Promising Young Woman, Cassie (played by Carey Mulligan), dies in the course of her revenge, and also had some beef with the film’s conclusion using the police as agents of justice. “Statistically speaking, cops are more likely to be assailants than resources,” she wrote, which if true would mean there are more violent crimes committed by police than there are total convictions for violent crime. You don’t have to be a blue lives stan to find that claim improbable, but I can see what she was going for.

It’s true that PYW is an untidy film, morally disorienting and oddly languid. It spends a huge amount of time on segments that don’t seem to advance proceedings, like the drug store dance to Paris Hilton’s “Stars Are Blind” (a scene I obviously love). This unevenness is something I actually like about Fennell. Peter Strickland, a director who is similar to her in his pursuit of aestheticism, tells extremely neat stories in his extremely perfect worlds and the result is frankly quite dull. (I haven’t seen In Fabric and maybe I’d enjoy it, but The Duke of Burgundy and Berbarian Sound Studio were both incredible achievements in boring me despite the presence of lesbian perverts and Toby Jones, two things I am usually a great fan of.)

I don’t think Fennell is interested in making films that unfold with satisfying tidiness: I think she’s a satirist who wants to make us squirm ourselves inside out. In PYW, the discomfiting truth is that our heroine is fatally self-destructive, and only seems like a heroine because her masochism has been dressed up (to herself as well as to us) as a righteous cause. When she is killed, it’s shocking: I didn’t see it coming, and it cracked my idea of the kind of story I was watching. It’s not Dirty Weekend. It’s In the Cut (the novel not the film).

But what happens to Cassie is right for the character, because it’s what she’s been seeking all the way through, as she repeatedly puts herself in sexualised situations where a man could easily murder her. It’s also right in a grim factual way, because she’s a woman attempting to physically tackle a man: what did we think was going to happen to her? That she’d buck all probabilities of human physiology and kill him with her bare hands?

Jude Doyle made a decent fist of smoothing off the rough edges and turning Promising Young Woman into a feminist manifesto, but it doesn’t really work, because the film is too uncomfortable to be settled into a neat ideological shape.1 As Doyle acknowledges, the people Cassie is most successful in hurting are all women — including herself. The film has stayed in my head for the last three years because it does something so compellingly vicious, not just to its characters but also to the audience. It makes us want what Cassie wants, then shows us that what she wants is truly, deeply heinous.

Listened

Cold War Kids, “Hang Me Up to Dry”

Saltburn pulls a similar trick. (And, yes, this newsletter is going to be crawling with spoilers.) Barry Keoghan’s Oliver is the hero, and so his wants become our wants. What does he want? Only to belong, it seems at first, as Oliver flounders socially in the posho pool of Oxford where everyone already seems to know each other from their private schools and ski resorts. The film gives us plenty of reason to mistrust Oliver, but the world he is part of is so convincing, his own slipperiness doesn’t immediately register. Oxford, 2007: the preppy clothes and the sticky pubs and the twitchy longing of young people thrown together.

Part of what makes it feel so right is the music — something Fennell nailed in PYW as well (see, again, the “Stars Are Blind” scene). The soundtrack is a perfect assemblage of things you would probably have heard at some point that year if you were moving in studenty circles (or in my case, going to the pub a lot with 20-something consumer journalists who all read Pitchfork). The self-conscious naffness of playing the Cheeky Girls at the college Christmas disco. The surge of Arcade Fire soundtracking Oliver’s moment of acceptance in the pub, or the jagged desperation of Bloc Party over a montage of him lusting for the gorgeous Felix (Jacob Elordi) across the class divide/staring at Felix creepily through windows.

And there’s this song by Cold War Kids, which I’ve been particularly enjoying, maybe because it’s the one I’ve heard the least — unlike a chunk of the soundtrack’s artists, Cold War Kids weren’t on the Pitchfork 100 so I didn’t torrent them and play them to death (obviously the Cheeky Girls weren't on the Pitchfork 100 either, but crucially they are shit). A big bluesy swagger of a song, sung from the perspective of the wronged party in a one-sided relationship using a… laundry metaphor? I’ll go with it.

Watched

Saltburn (in theatres)

The other reason to watch Saltburn in a theatre, besides seeing the gorgeous visuals at full scale, is that you get to enjoy the shocked tittering of fellow viewers. There’s a particular moment when Fennell announces the game has changed: Oliver has worked his way into Felix’s family pile as a summer guest, and his simmering obsession with his friend begins to gain the confidence of true sociopathy. Oliver secretly watches Felix in their shared bathroom, masturbating in the bath; then when Felix leaves the room, Oliver goes in and drinks the water.

And he keeps drinking it, tongueing it out of the plughole with a lascivious fervour in a scene that feels like it goes on for about seven minutes. It’s as close to a literal ass-licking as you’ll see in a certificate 15. Fennell treats the incident like a Stewart Lee punchline: the point is not just for you to get it, but for you to stay with it long enough that laughter turns to horror turns to laughter again turns to something else. It’s the same sadism she applied in the death scene of Promising Young Woman: you will sit there for as long as it takes, because your discomfort is her art.

It’s an especially cruel scene to linger on, because it’s so incompatible with the imaginary film many critics seem to have wanted Saltburn to be. “The movie does for ‘posh’ what Soul Plane did for ‘ghetto’: luxuriate in what it’s pretending to blow up,” tsked the New York Times, as though Fennell’s only justifiable purpose must have been to mock the wealthy Felix — something it does very effectively, by the way, but not to the point of sanctifying Oliver. Oliver is, undeniably from this moment in the film, something sinister: he wants to devour Felix and Felix’s family, and he will do so.

Some critics dislike the film’s portrayal of Oliver: “Saltburn’s overarching message seems to be profoundly anti-upward mobility”, complained Alexandra Jones in the Evening Standard. James Marriott in the Times wrote that, “With the complacency characteristic of her class, Fennell never pauses to reflect that a person like Oliver might not be that interested in befriending aristocrats.” Actually, there is a person like Oliver in the film who isn’t interested in befriending aristocrats: the angry maths nerd Oliver pals up with at college and then discards. He isn’t a nice person, but he’s undeniably got the edge on Oliver.

Oliver fawns over the poshos just as much as they think they deserve to be fawned over, and their susceptibility is their downfall. They are weak, complacent, careless, cruel, their soft bellies bared to the knife, their privilege trapping them in grotesque dependence. Oliver is exactly the monster they deserve, and he will punish them far beyond what their sins merit.

Some things about Saltburn don’t quite work. The last act is somehow both dragged out and overly compressed — my instinct is that you could have cut some of the Oxford scene setting and given more breathing room to the Kind Hearts and Coronets business, but equally you could have binned the Swole Ripley stuff and devoted more time to the well-observed social satire. I’d also have taken at least twice as much Richard E Grant as it contains.

But I don’t really buy the complaints that Saltburn somehow “fails” as a satire on the upper classes, and slightly suspect that the people saying that merely wish that Saltburn didn’t also satirise middle class aspirancy. (Including a sharp jab at pretending to poverty as a tactic of the climber: “So real,” as Felix’s pitiable sister Venetia says, somewhat mistakenly, to Oliver.) Class can only function if there are at least some Olivers out there who do, in fact, want to lick their way into the inner circle.

Read

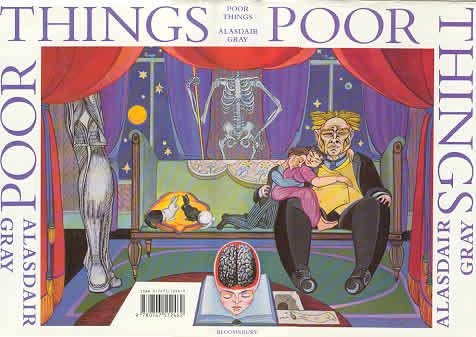

Alasdair Gray, Poor Things (Penguin)

I was going to round out my Saltburn obsession by reading a Waugh or a Mitford or something like that, but instead I picked up Gray’s Poor Things to re-read after watching an early screening of the (incredible, you will love it) Yorgos Lanthimos adaptation at the Bath Film Festival. I’ve written a celebration of the novel — one of my absolute favourites — that should be in the Sunday Times next weekend.

That piece is mostly about the canny way Poor Things satirises men’s horny failure to comprehend female subjectivity, but Gray was a great analyst of class as well as of lust. Poor Things — with its Frankenstein-cribbing story of creation and self-creation — includes some fantastic teasing of the British social system, particularly directed through and at the socially mobile trainee surgeon Archibald McCandless.

“Don’t scorn a polite appearance because many fools, snobs and scoundrels have that,” a patronising (but not unhelpful) lecturer tells him. “You will not find us a bad set of people, and will gradually fit in by a process of instinctive imitation.” You can imagine someone giving the same advice to Oliver, and you can imagine exactly how he would have received the “not a bad set of people” comment.

Gimme, gimme more…

I sat in on the Sunday Times comment page this week and tried to explain why Nigel Farage is such a bust on I’m a Celebrity this year (answer: he’s an intensely vain, selfish man whose selfishness turns out to be greater than his vanity when he’s in a tank full of eels)

Much more fun: I also did a set report from Aardman Studios on the brilliant Chicken Run sequel

The curse of the Von Erich wrestling dynasty (I watched a preview of The Iron Claw this week and am very excited for it)

Doyle’s Substack is now called Hamish McKenzie Killed Someone, because Hamish McKenzie is the founder of Substack and Doyle is extremely angry that Substack hosts content with which Doyle disagrees. This is a very dumb position to take but I do kind of applaud the pettiness, and also the commitment to the bant shown by Doyle publishing a near-daily newsletter titled “Hamish McKenzie Killed Someone” for three months in 2022; although I even more applaud McKenzie for leaving Doyle to just tantrum it out rather than imposing a ban.

I haven’t seen the film, however your description of the bath scene had my toes curling! Not one to watch with my son and his g/f, I feel?