I don’t want this to be a mad-at-the-Oscars kind of a newsletter, but unfortunately I am mad at the Oscars. What the hell is going on in the Academy’s collective brain for them to nominate Annette Bening for obvious award-bait lie-a-thon Nyad, but not Margot Robbie, whose Barbie is a performance of comic timing and physical control for the ages? (I’m not joining in with the irritation that Ryan Gosling was nominated for Ken while Robbie was overlooked, because I want him to win — although I’d also be very happy if it was Mark Ruffalo for Poor Things, and can honestly live with the probably inevitable Robert Downey Jr for Oppenheimer victory.)

And no Greta Gerwig nod for best director! I actually think the feminist outrage is being overdone on this: the fact that Justine Triet was nominated for Anatomy of a Fall suggests this is less about Gerwig being a woman, more about the Oscars’ traditional anti-comedy and anti-populist bias. Which man should we bump to make room for her, anyway? Scorsese is the only one I can imagine making a case for, and that seems mad.

Also, please can we all agree that Barbie is a funny movie with incredible production design, and not a sacred text of the women’s movement? Calm down, Hillary Clinton. Some of the commentary about how Gerwig doesn’t deserve a place on the list does strike me as sexist, though, leaning on the plainly idiotic idea that a “girl movie” like Barbie is somehow less of a labour than a “man movie”. Absolutely shut up unless you’ve successfully shot a musical number on a par with “I’m Just Ken”.

Then again, the fact that I’ve got such strong feelings about the 2024 Oscars suggests that we’ve had a very good year for films. Looking back over the best picture nominees, the last time I’d unhesitatingly go to the cinema for every single thing on the shortlist was probably 1976. I’d love to hear which films you’re rooting for — personally I’m team Poor Things/Oppenheimer/Killers of the Flower Moon/Barbie/Zone of Interest (see below), with Anatomy of a Fall, The Holdovers, Past Lives, Maestro and American Fiction still on my to-watch list. Shout out your faves in the comments. (And check out last week’s for some great Under the Skin chat.)

Listened

Roxy Music, “In Every Dream Home a Heartache”

Since I’m stripping the title down for parts, let’s have a listen to the real thing. What a brilliantly weird, campy band Roxy were. I laugh every time I hear Bryan Ferry deadpan “I blew up your body/ But you blew my mind”, and then get swept up anyway in the ecstasy of the coda. If the song’s narrator had this reaction to an inflatable doll in 1973, he’d probably have gone absolutely potty if he ever met a 2024 sexbot.

Watched

The Zone of Interest (general release from 2 February); Priscilla (general release, just about at this point)

I didn’t think I had much to say about Priscilla beyond the brief note in last week’s newsletter, but I thought about it a little more after watching The Zone of Interest. Without wishing to draw an equivalence between the subject matters, both use a meticulous recreation of the past and a naturalistic performance style (in Zone of Interest, achieved using hidden cameras — a technique Jonathan Glazer previously used on Under the Skin’s crowd scenes) to revisit an appalling event in twentieth century history.1

Obviously the Holocaust is several orders of magnitude more appalling than Elvis grooming a 14-year-old girl, but I think both films are an effort to get beyond disgust and into the human detail of acts it would be nice to think are unimaginable. To reinvest evil with its proper banality, if you like. Both are, it’s fair to say, low incident movies. As the audience, you’re bearing witness to what could almost be random portions of everyday domestic life — in Graceland, in the Höss family villa at Auschwitz. They both just kind of stop, rather than hitting a narrative crescendo.

we experience the history we know refracted through its influence on the home

The action is outside, and we experience the history we know (Elvis’s creative decline and crappy movies and relentless performances, the Holocaust; and again I am definitely not saying are those two are the same) refracted through its influence on the home. When Höss is promoted, we see his wife’s anger and anxiety about the potential disruption of her blissful life as “queen of Auschwitz”. We hear the family talk about missed birthdays and anniversaries. But we know that Höss’s reassignment is another ratcheting up of the machinery of killing.

The difference is that I found Priscilla boring, and The Zone of Interest wholly absorbing and deeply disturbing. I’m curious about why, because it isn’t about my preexisting level of interest in the subject matter, and nor is it about the quality of the performances (both casts are excellent). This is my theory: I think The Zone of Interest succeeds because it fully commits to its interest in evil, whereas Priscilla skirts around the edges, examining its (perfectly manicured) fingernails.

Sophia Coppola wants to be making a film about Priscilla herself, but the film’s centre of gravity keeps lurching back to Elvis. He is just much more interesting than his doe-eyed child bride, and Jacob Elordi finds a man under the calcified layers of myth. What would being as famous as Elvis do to you, when no one had ever been that famous before? How can a man be so powerful that he lives surrounded by yes-men (and a single yes-girl), but so weak that can never make his own decisions? Elvis drives his own tour bus, but he never gets to decide where it goes.

There’s an often-expressed article of faith that we (as creators and as audiences) should be more attentive to the victims of wrongs than the perpetrators; that to develop a theory of mind about an evildoer is to be deficient in sympathy for those to whom evil is done. The shadow of this thinking is probably behind Coppola’s decision to call her film Priscilla — and not Elvis and Me, which is the title of the Priscilla Presley memoir it’s based on. In fact, you can find this exact criticism in the NYT’s rather stupid review of The Zone of Interest by Manohla Dargis: “like so many other movies, mainstream or not, this one is fascinated with its villains, far more than it is with their victims, whose suffering here is largely reduced to room tone.”

There’s an often-expressed article of faith that to develop a theory of mind about an evildoer is to be deficient in sympathy for those to whom evil is done

As an ethical stance, this is not entirely void of merit. If you tell Elvis’s story as one of singular genius and never reflect on what that “singular genius” did to Priscilla, you’re committing an incredible disservice to her individually and the truth in general. But stories of isolated victimhood become gratuitous, even pornographic (“girl menaced by faceless man” is the plot of Texas Chainsaw Massacre). Priscilla is too low-key for that charge to stick, but it’s still dull to spend so much time with someone who is mostly soaking up a lot of bad treatment while looking very pretty.

In The Zone of Interest, you do see Höss’s victims: there are Jews working in the villa as domestics, Jews working as labourers, screams — and smoke — that drift over the high walls of the garden, a bone in the river. We see them, but the Höss family do all they can not to. It’s not the most distressing thing in the film by any means, but I found it deeply shocking when, in an early scene, an Auschwitz inmate delivers a parcel to Frau Höss, and she does not even acknowledge him, never mind say thank you. The idea that this reduces the victims to “room tone” suggests a woeful lack of confidence in the moral capacity of the viewer.

I have to ask what approach Dargis would have found acceptable. Lingering close-ups on piles of starved Jewish corpses? Did she want to actually watch Höss raping a young Jewish woman, Sansa in Game of Thrones style (an incident which is signaled in the film by the woman taking her shoes off and letting her hair down, followed by — horribly — a scene of Höss washing his penis in a sink)? Probably not! Which makes me wonder whether the underlying objection is, in fact, to the portrayal of the Holocaust at all.

The Zone of Interest humanises Rudolf and Hedwig Höss, but (obviously) not to invite our sympathy or approval. It is simply true that they were not outlandish monsters. They operated within norms of the society they belonged to. They loved their children. They wanted a good life, the respect of their peers, security, purpose. To dehumanise Nazis is to commit to a gross form of moral self-flattery, because the kind of evil they engaged in is, obviously, human. Definitionally human, even: no other creature is capable of industrial genocide.

the kind of evil Nazis engaged in is definitionally human: no other creature is capable of industrial genocide

Right at the end of the movie, Glazer does something extraordinary: he breaks out of the world of the Hösses and jumps forward to the present day, to footage of the Auschwitz Museum being cleaned ready for the next tranche of visitors. Industrious, impassive women wearing lanyards run their cloths over the glass covering uncountable piles of empty shoes, a few of them carefully paired as though the owners hoped for only a temporary separation.

“Is this a bravura instance of jazz filmmaking, an unexpected formal flourish designed to catch the audience off guard? Or is it something humbler than that, an admission of artistic defeat?” wonders Giles Harvey, in a (non-stupid and in fact very good, Dargis could have done herself a favour and read it) interview with Glazer for the NYT. This is what it made me think: do the dominant ways of remembering the Holocaust remember enough, or really remember it at all? Do they put back together the whole of what happened?

When people play the game “what would I have done if I’d been alive when the Nazis came?”, it’s usually implicit that they wouldn’t have been a Nazi themselves — that their feet would have been in the vacant shoes. But roughly one in three voters supported the Nazis in 1932. If you’d been alive when the Nazis came, there’s a non-zero possibility that you’d have been one of them. It’s easy, and comforting, to imagine yourself in the position of history’s oppressed. It’s equally likely, though, that you might fall on the other side.

Read

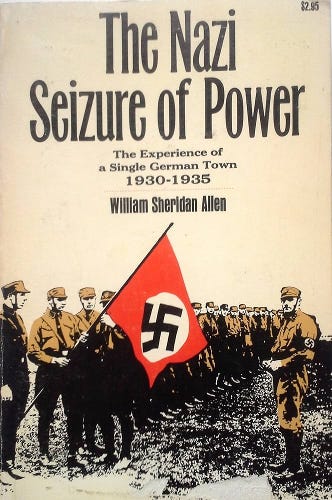

William Sheridan Allen, The Nazi Seizure of Power: The Experience of a Single German Town 1930-1935 (Eyre & Spottiswoode)

If you remember me recommending The Ruin of All Witches, you might be aware that I’m a sucker for a history of a small town — Montaillou, on the life of a French village during the inquisition, is the classic. It’s not a coincidence that, like those two books, The Nazi Seizure of Power focuses on an era of legalistic terror. Those spasms do, after all, generate enormous quantities of paperwork, capturing lives that would otherwise be forgotten in testimonies and confessions. But it’s also because those spasms are social phenomena, and it’s right to view them in that context: as ensemble dramas rather than bildungromans.

The proper question to ask isn’t “why would anyone become a Nazi?” Really, it’s “how, after Nazi rule was an inevitability, did some people continue to resist?” There’s a certain cussedness to choosing a moral life — even, in some of the cases of the citizens of Thalburg (a fictional name for the real town of Nordheim, because William Sheridan Allen published this book in 1965 and those he interviewed did not wish to be identified) self-destruction.2 By 1933, even passively demurring from Nazism meant unemployment, penury, ostracism and harassment. Open opposition meant the concentration camp.

By the time the strongman appears, he’s already been called into being by the general decay of the state

The damage, though, began long before the Nazis emerged as an electoral force. Germany in the 1930s was already home to a febrile mix of passionate political engagement (often expressed in street fights) and general exhaustion with civic institutions. By the time the strongman appears, he’s already been called into being by the general decay of the state. After recounting some of the more vituperative coverage in the town’s main social democratic paper, Sheridan Allen writes:

All of this made interesting reading for Thalburgers and possibly increased the Volksblatt’s circulation. In some cases it might even have affected votes. But its chief effect was to debase the nature of politics and to destroy the foundation of trust and mutual respect without which democracy cannot succeed. When politics becomes a matter of vilification and innuendo, then eventually people feel repugnance for the whole process. It is the beginning of a yearning for a strong man who will rise above petty and partisan groups. The Nazis were to exploit this feeling fully, and though they contributed richly to the rise of partisan acrimony, they were also the first to pronounce “politician” with every possible tone of scorn and sarcasm.

Of course, I read that and thought about Trump. It is easy, from my social democratic perspective, to say that the rot of America started with Trump. But in the aftermath of the 2000 elections, it was the left, not the right, questioning the legitimacy of the result and looking for salvation in faulty voting machines. The “foundation of mutual respect” has been a long time crumbling. Anyway, who’s feeling perky about the 2024 presidentials?

Gimme, gimme more…

Speaking of dolls (which I was before all the Nazi stuff), I wrote for UnHerd about Only Say Good Things, the memoir of Hugh Hefner’s last wife, Crystal Hefner — stick a pin in the #MeToo revisionist memoir cycle, it’s done. And Hadley Freeman was very funny on the same for the Sunday Times.

While I’ve got the women of Playboy on my brain (and because I watched the Netflix documentary about her): it is literally mindblowing that celebrity sex tape victim Pamela Anderson married celebrity sex tape leaker and entrepreneur Rick Salomon (of the Paris Hilton tape), not once but twice. MINDBLOWING. MIND. BLOWING.

By me for The Critic: a brief history of pop star outings.

The Daily Beast ran a rundown of some of Toxic’s juiciest bits.

Do not recommend reading about the latest Vince McMahon allegations because they’re extremely upsetting, but here they are.

Julie Bindel on the boy she knew at school who grew up to be a sadistic killer.

Look I’m all for people talking about Poor Things (last week’s comments have nudged me into writing up my thoughts on it for next week), but never have I ever seen a more exhaustive attempt to flatten a movie into dullness than this round table. I thought the subhead “Ultimately, she is a woman born into financial privilege” would be the nadir, but somehow it keeps going for several thousand more incredibly annoying words.

I saw Buster Keaton’s Go West it for the first time last week (in fact, I saw a Buster Keaton for the first time last week). Someone really should have told me it’s the touching love story of a man and his cow!

I continue to be a huge fan of the Jonathan Glazer method of adaptation, in which you keep the title and strip out pretty much everything else. Zone of Interest is based on the Martin Amis novel of the same title, but if they didn’t share a title, you wouldn’t know it.

I thought about this while I was in the Red Museum in Dubrovnik this summer, watching video interviews with political prisoners who survived the Communist labour camps. These opponents of totalitarianism were not necessarily “good men” — in fact being “good” is one of the last qualities you’d probably ascribe to many of them. In many cases, they seemed mostly defined by a lack of the kind of pro-social instincts that nudge people into conformity.

That Guardian roundtable made me reflect on one of Helen Lewis’s recent substacks about the politicisation of arts criticism and what a stifling bore it is to read aspiring intellectuals praise or condemn a film based on whether it reinforces their own moral viewpoints.

How difficult is it to engage with the a piece of art based on whether it achieves what it sets out to achieve, demonstrates great technical craftsmanship or ENTERTAINS rather than whether it flatters us and strokes our fragile egos?!?

I never thought I’d reach a stage in my life where I looked back fondly on the idea that art should challenge our preconceptions, but here we are, with 75% or critics seemingly determined to praise and reinforce only the dullest and least imaginative of achievements, and poised to condemn anybody who achieves something vaguely interesting.

It’s called civil inattention, the ability to ignore people in plain sight. Except of course the Höss family were engaging in hideously uncivil inattention. Such a great essay, missus, thank you.