Some excellent postbag in response to last week’s newsletter. Niall Boyce — former editor of The Lancet Psychiatry — had this fascinating commentary on the subject of SSRIs and assexuality:

Interesting link to the blog on SSRIs/asexuality. I'm not entirely sure about this hypothesis — some of the facts and figures seem off at first glance (e.g. the line about the Royal College of Psychiatrists “admitting” to using SSRIs for sexual offenders links to a presentation by someone at a big general RCPsych conference, the gist of which is that there is little evidence for their use in this context).

That being said, there is a grain of something here (not least because SSRIs have been used to treat conditions such as premature ejaculation). I think that psychiatrists have for various reasons not listened as carefully as they might to patients reporting side-effects and withdrawal effects of antidepressants in general. Some of this is because of pharma marketing, perhaps. Also, trials might not have been designed with the length of follow-up needed to fully assess these issues (e.g. as they are going for three-month treatment endpoints), and it could be the case that these side-effects are not actively searched for, recorded, and reported. Something similar happens with adverse event reporting in psychological trials, which is traditionally very poor. Absence of evidence has too often been taken for evidence of absence! Fortunately, the College under its previous president Wendy Burn began to address SSRI issues.

Then there is the possibility that clinicians might pass over the whole issue of sexual side-effects as they aren’t confident asking about them, or think they aren’t important in the greater scheme of things. Which is a bit odd, considering modern psychiatry starts with Freud who couldn't stop talking about sex. Moreover, sexual side-effects are an issue not just with antidepressants, but with antipsychotics, and they really matter to patients (#4 of top ten priorities).

While I doubt that SSRIs are the only or even the major driver behind asexuality, there is an important lesson here regarding how we evaluate and monitor treatments and assess risk-benefit. Then there is the broader issue of how “mental health” discourse interacts with self-evaluation and identity (Lucy Foulkes’s What Mental Illness Really Is is brilliant on this).

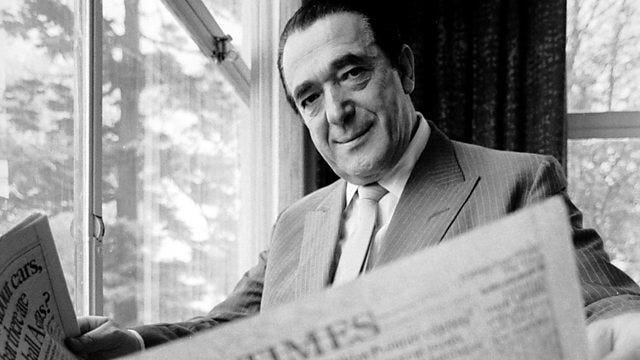

Meanwhile, Francis Wheen poured fuel on the fire of my Robert Maxwell fixation. “Are you aware of Eleanor Berry’s bizarre book?” he writes. “The description here will give you a flavour, though it doesn’t mention the book’s account of how Cap’n Bob used to seek Eleanor’s advice on whether he should chastise the young Ghislaine with a cane or a horsewhip.”

As a journalist, Francis ran the Maxwell gauntlet IRL while the big old crook was alive, and made an excellent documentary about Maxwell’s abuse of the libel system (after Maxwell’s death, for obvious libel law reasons) which you can watch on YouTube (part one, part two and part three). You can also listen to a Maxwell-themed edition of the Private Eye podcast, featuring Francis in conversation with Ian Hislop. What a treat, and how fortunate that the days of dubious oligarchs burying the press under a blizzard of legal threats are behind us (subs please check).

Listened

Desert Island Discs, Robert Maxwell (BBC Sounds)

Surely that is enough Maxwell, and yet somehow, no it isn’t. Maxwell did Desert Island Discs in 1987. “If our castaway needed the money, which he doesn’t, he could sell his life story to Hollywood for a blockbusting miniseries,” begins Michael Parkinson. “It supports the theory that often truth is more exotic than fiction.” Which, if this were part of a script about a self-invented fraudster spiraling into bankruptcy rather than an interview with a real life one, you would consider a bit on the nose in terms of dramatic foreshadowing.

The record choices feel perfunctory: a lot of Mozart, some Beatles, a Churchill speech, the sense of Maxwell selecting the things a cultured (but unstuffy!) patriot might select. Of his peasant childhood, Maxwell says he remembers feeling “hungry” — a hunger he apparently never stopped trying to assuage, ballooning his body grotesquely. At the end, Parkinson asks Maxwell if he would try to escape his desert island. “Not for a little while,” says Maxwell, who must have already started to ask himself what way out there could be from the boiling pot of his own businesses.

Watched

Maxwell (YouTube)

This 2007 TV movie is not great for a few reasons, and even if it wasn’t in terrible resolution (anyone further away than a closeup looks like a thumb), I would not recommend. One, it invests far too much time in exposition to explain the mechanisms of Maxwell’s frauds. In terms of drama (rather than journalism), it doesn’t matter exactly how he stripped what assets from which company — what matters is that, by 1991, Maxwell was under extreme pressure from his own criminality, and sliding towards his slip/suicide on the yacht.

Two, budgetary constraints mean there is no yacht: the drama ends with a real “Poochie died on the way back to his home planet” moment, cutting from Maxwell waiting on his helipad to his son Kevin announcing Maxwell’s death. This is unavoidable, but a shame when the great dramatic question of Maxwell’s life is: jump or accident? How much did he recognise the consequences of his actions, even as he was maneuvering himself beyond the point of no return? Was he fooling himself as much as anyone, even at the very end? The role of Maxwell’s wife Betty might have been used to deepen his character, but here Patricia Hodge is both underused in a thinly scripted part, and overused given she has chosen one of the least convincing accents I’ve ever heard.

I watched this mostly out of curiosity about how a drama would show Maxwell, because he strikes me as one of those figures — like Thatcher or Trump — who is already so tantamount to caricature, it is very hard to make a character of them. Maxwell looked bizarre, sounded bizarre and lived in such bizarre defiance of any norms, it’s a challenge to make him feel real. Brilliant Roger Allam has a cameo as Maxwell in the Tetris movie, but the character comes across as an animate fatsuit with eyebrows. By contrast, David Suchet as Maxwell in 2007 is excellent at the domineering presence, the flashes of vulnerability, the voice that was a campy imitation of the British ruling class — but not vile enough.

Maxwell at this point was morbidly obese, his ankles swollen and blackened, suffering constant pain.1 Suchet looks bulky, but not like that, and when the film gestures to his revoltingness (for example, Betty challenges him at one point about the state of some towels, and Maxwell answers that he has trouble cleaning himself, ick), it feels put on, because the rest of the time there’s little sense of this gross physicality. Bluntly, other characters are not reacting to him as though he is disgusting: we’re just being intermittently told that he is.

Read

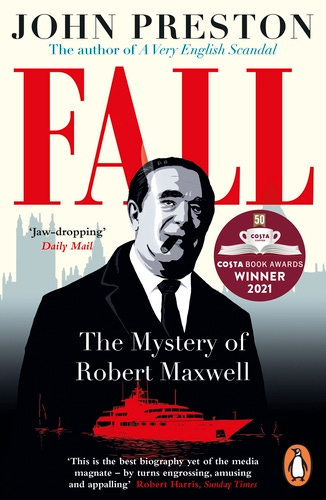

John Preston, Fall: The Mystery of Robert Maxwell (Penguin)

I did say I was obsessed. I read this not long after it came out, when I was writing about Maxwell’s daughter Ghislaine; I’ve been revisiting it on audiobook recently. Parkinson was right about Maxwell’s life being relentlessly cinematic. He lived pincered between genres: there was the rags-to-riches biopic Maxwell narrated for himself, with war movie interludes and later acts of capitalistic swashbuckling. And then there was the psychological horror he lived in: tormented by his own insecurities, tormenting his family and his employees in turn.

A monster, but a monster made by the twentieth century, and maybe the monster the British class system deserved (though the Mirror pensioners certainly didn’t). A monster whose mania for self-invention would have fit perfectly into our own time, I suspect — an early identity entrepreneur. The book was optioned by Working Title on publication, so hopefully someone has already been wrestling with the problem of how you dramatise Maxwell. Hit me up if this is you, I have a lot of ideas!

Gimme, gimme more…

At this point, the circumstances of the Tom Cotton NYT oped have surely been more thoroughly documented than any column in history, but Adam Rubenstein’s version is very much worth reading. You’ll be amazed (no you won’t) to hear that opening sandwich story was treated immediately as a subject of derision by NYT insiders (way to convince the world you’re not a bunch of petty sandwich bullies!), who have strangely had nothing to say since the Atlantic confirmed that it had indeed factchecked the anecdote with multiple sources before publication.

And old fave that I was reminded of this week: there’s a horrible truth about the internet contained in the fact that The Awl no longer exists but the “chum” clickfarms described in this article continue to thrive.

“His willingness to suffer this way certainly demonstrated his ‘determination and sincerity,’ to use Nhat Hanh’s phrase. It also showed his numbness to the suffering of others: His cinders should inspire action, but the much larger piles of cinders of whole families in the Kfar Aza kibbutz somehow should not.” Graeme Wood (The Atlantic) on self-immolation as protest.

I cannot get enough of this herogram to self from a former Vice writer. Come for the absolutely demented levels of self-aggrandisement (“I remember the London office as somewhere where almost anything could happen, where a young, hungry and experimental staff created a style of film-making and writing that […] would go on to influence much of contemporary British media”), stay for the terrible writing (come on, who says “boozer” outside a Guy Ritchie film?), never forget that this is an encomium for basically a skank version of Gawker.

Related, from 2011: “Just because you put on a fucking safari helmet and looked at some poop, doesn’t give you the right to insult what we do.” It’s fun to imagine the volume of furious typing David Carr might have done if he’d lived to see the sandwich discourse.

I’ve always assumed that the following gag from Fit the Seventh of The Hitch-Hiker’s Guide to the Galaxy was about Maxwell, although my cursory research for this newsletter has turned up no support for that belief beyond the fact that “Maxel” sounds a bit like “Maxwell” (I’m not sure whether, at the time of broadcast in 1978, Maxwell — then a big deal in science publishing but pre-Mirror — would have been recognisable enough to be worth mocking like this):

ARC ONE Look at the visiscreen — see that big white city there the whole blooming thing is just Hitch-Hiker's offices, palm trees — and so many swimming pools you need a bloody gondola to get about.

CAPTAIN Well that’s success for you, isn’t it?

ARC ONE Is it? Is it? Well I ask myself. All gone soft haven't they — Hitch-Hiking, what do they know about it? Get one of that lot to stick out their thumb, it would probably fall off. I mean. It’s all just fat cat business now. What’s the name of that bloke who runs it now?

CAPTAIN Maxelcat.

ARC ONE Well you know what they say don’t you. They had to move to a bigger planet because he got so fat he kept sliding off the old one.

Of course you read The Awl! I miss it so much. The comment section was as entertaining as the articles.

Someone who would be fascinating re Maxwell is Helen Liddell, now in the Lords, who was his press officer at the time he "rescued" the Commonwealth Games. I bet Helen has a few tales to tell.