Slight change to regular programming, because this week we’re not going to be talking about some junk from the noughties: this week, we’re talking about the BAD ART FRIEND.

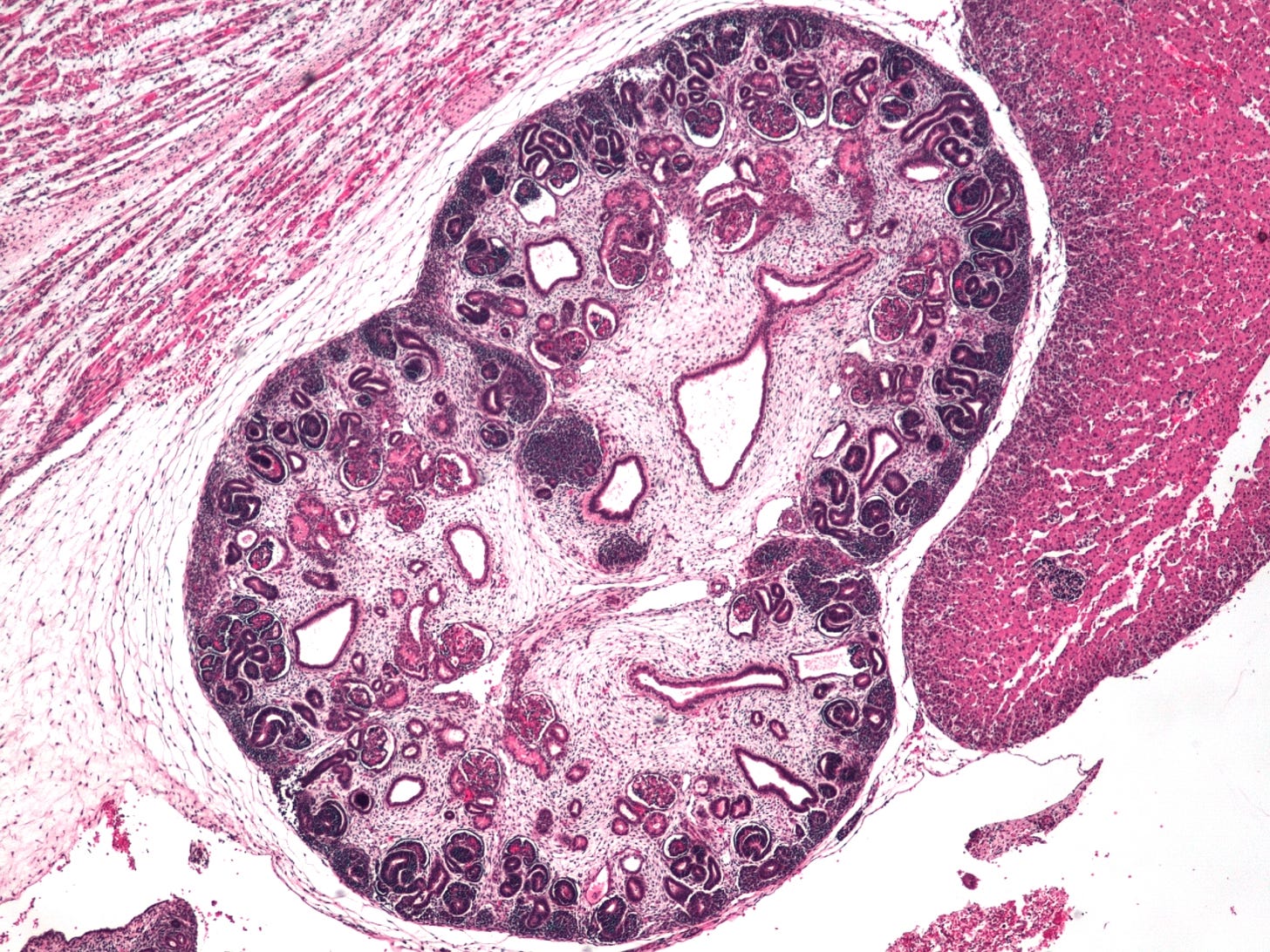

If you haven’t encountered BAD ART FRIEND yet, start by reading the NYT article. If you’ve read it, skip to the first section break of this newsletter. It you haven’t got time to read it right now, the Cliff notes version goes like this. Two female authors are part of the same writing group. The first, Dawn Dorland, makes a “non-directed” donation of a kidney — i.e. she gives an organ to a person she doesn’t know, in an act of pure altruism. (But how pure can altruism ever be? This is a key question of the BAD ART FRIEND discourse.)

The second, Sonya Larson, does not donate a kidney. Instead, she lurks in the private Facebook group Dorland has set up to keep friends informed and rally support as she goes through the donation process. Larson does not respond to the group posts. But she does write a story about a woman (who is white, like Dorland) who makes a non-directed donation of kidney that ends up in another woman (who is Asian-American, like Larson — and how much that racial parallel matters is another key question of the BAD ART FRIEND DISCOURSE).

The kidney donor in the story is not sympathetically portrayed (this according to the NYT account, anyway). Her act of altruism is cover for a need to be applauded. She is controlling about the recipient: she wants her gift to be redeeming for both parties, but the recipient doesn’t want to be redeemed. She wants to carry on living her not especially laudable life. Dorland heard about the story, in broad outline; she wondered if it was based on her, but Larson said only in the very loosest way, inasmuch Dorland had led her to think about kidney donation as a topic.

Then Dorland read the story and saw that the letter written by the fictional donor to the fictional recipient took several phrases — a lot of phrases, actually — from Dorland’s own letter to the recipient of her kidney. What happens next is a mess of legal actions, charges of plagiarism, accusations of white privilege and claims for the freedom of the artist to do whatever their art requires. Read the article, it’s very good.

Hopefully I’ve given the impression that BAD ART FRIEND is a compelling piece of journalism, but I haven’t really explained yet why it’s upskirt-adjacent. One of the brilliant things about it is that it invites you to see Dorland and Larson as hero or villain according to your own priors; and then it relentlessly, skillfully unpicks whatever view you’ve taken. My immediate reaction was that it was Dorland who had overstepped by taking offence to being mined for fiction: as the Sleater-Kinney song goes, “don’t tell me your name if you don’t want it sung.” Tangle with an artist, and you know you’re going to get turned into art. You might as well be the Gingerbread Man asking the fox not to eat you.

When a woman named Alexis Nowicki claimed Kristen Roupenian’s short story “Cat Person” was based on her, I firmly took Roupenian’s part. Roupenian could have — should have — tactfully obscured some of the inspiring details she agrees she took from her passing knowledge of Nowicki. But the story is not “about” the real-life Nowicki: it’s about the interiority of a fictional character. Roupenian didn’t have access to Nowicki’s inner life (they never actually met), so she was never in a position to “steal” that. Instead, she did what authors are supposed to do: she made it up, so well that Nowicki felt deeply seen — but then so did a lot of people who read that story, because it was a very well-observed piece of fiction.

All artists use life as the raw material of invention. How could you not? The words we have, the things we know about relationships, the objects we are able to describe — they are available to us because they exist prior to our imagination. But for some artists, they way they use life is tantamount to an act of aggression. When I reviewed Chris Kraus’s biography of Kathy Acker for Literary Review, I also read Acker for the first time.1 I found her cut-and-paste technique breathlessly thrilling when she applied it to works (Great Expectations is one novel she put through the mincer to her own ends), but horrifying when she used it on people. From my review:

Acker realised – and this is probably the illuminating insight of her work – that her sexuality could be weaponised. […] Blood and Guts in High School (reissued to coincide with this biography) is a case in point. It opens with a series of exchanges between ten-year-old Janey and her father. They are in a sexual relationship and he is withdrawing from it. It is shocking and gratuitous for sure, but somehow more shocking is that Acker based this section extensively on the dissolution of her relationship with her second husband, Peter Gordon. By putting his words in the mouth of an incest-raping father, she puts her ex distinctly at a disadvantage.

If I’d read Blood and Guts when it was published in the 1980s, I wouldn’t have known that Janey’s father’s words were actually Peter Gordon’s, though. (I’d also have been pretty traumatised given the fact I was a child in the ’80s.) That information is only available to me because I’ve read the Kraus. But the skin between private and public is a great deal thinner now. Nowicki realised Roupenian had pulled certain details (inconsequential ones, in my opinion, but still) from her Instagram. And the words of Dorland’s which Larson put into an unsympathetic character’s mouth were not spoken: they were written, in a letter that was shared as a (private) Facebook post.

For some, the fact that Dorland publicised her donation on social media makes it fair game for fiction. To me, the fact that it is possible for people who knew Dorland to identify these as her words makes the intrusion more unforgivable. Larson took something from Dorland — knowingly, purposefully, and according to the chatlogs available, with the intent to wound her subject. Dorland’s kidney was a gift to a stranger. But her words were snatched from her by someone she had supposed was her friend.

When I was studying The Wasteland at university, I was taught that the word “plagiarism” comes from a Latin word meaning “kidnapping” — or really, rape, because what would you snatch a woman for if it wasn’t for that? Going in for etymology is a dicey was to do readings (who really hears the history of a dead language in every single word?) but here it seems to matter, because it suggests the intimacy of the violation perpetrated when you take someone’s words and life and make it into art. And this is why the BAD ART FRIEND DISCOURSE has nagged at me while I’ve been working on Upskirt this week.

For me it’s not really a story about interpersonal betrayal, or about copyright, or about artistic ethics (although, full disclosure which may not be necessary given how much I’ve shown my hand by this point, Larson’s plagiarism — and cruelty — crossed the line for me, and made her story something I couldn’t defend). It’s a story about how much you’re entitled to take from someone because she has made a bit of herself available. That question of entitlement, of boundaries, of who is allowed to say “stop” and who is assumed to have signed away all her consent — that is the core problem, of the upskirt decade, and a problem that seems in no danger of imminent resolution.

Sarah x

There’s every chance that the BAD ART FRIEND DISCOURSE has been extended beyond everyone’s patience by now, but if you’ve got more appetite for kidney chat, I’d love to read your comments or emails.

Gimme, gimme more

It’s all go in the battle of Little Mix vs Jesy Nelson. Not content with proxy warfare via dog Instagrams, Nelson’s ex-bandmates have accused her of “blackfishing” (i.e. altering her appearance via tanning, perming and fillers to “look black”); Nicki Minaj (who has a credit on Nelson’s single) has defended her, and look, if you can’t trust the woman whose cousin’s friend’s swollen balls dominated the international news cycle for a week last month, who can you trust?

Brace yourselves for the Adele comeback! She’s written about her divorce in an effort to, she says, explain to her son why she “chose to dismantle his entire life”; but a lot of the takes are, inevitably, going to be about her weight loss.

The problem with Liz Phair’s self-titled album is that it’s an irredeemable piece of shit, says Freddie deBoer. I have no strong opinions about Liz Phair’s self-titled album, but I enjoyed this furious takedown of the Pitchfork critical style so much that I’ve spun my next Critic column out of it.

If you want to read something by Kathy Acker, I recommend her inexplicable encounter with the Spice Girls from the Guardian in 1997. Wow they were a thing, weren’t they?