On BarPod, Katie asked me a good question: why do some people who get cancelled go mad, and some don’t? By “go mad”, I mean they become fixated on their own victimhood. They become obsessive about the issue that led to their cancellation, and unable to disassociate the injustice they feel they’ve suffered from the justice of their cause. And they grow ever more radicalised: on the episode, we were talking about gender criticals who’ve advanced into far-right rhetoric, but the phenomenon of going mad on the internet is ideology-neutral. Any kind of extremism will do.

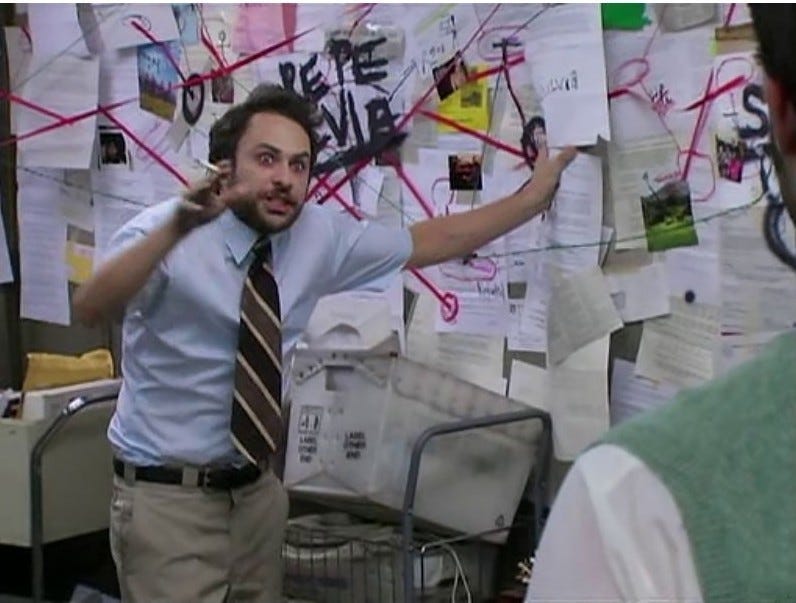

There are three essential elements to going mad I think:

a sense of grievance

a lack of fundamental principles

a strong identification with the victim role

First, the sense of grievance. This is the inciting incident. The person who goes mad on the internet has suffered a loss — often with genuine personal and professional consequences. But that, in itself, is not sufficient, because lots of people suffer similar losses without becoming Tommy Robinson-adjacent. (Of course, another factor is that some people start out pretty Tommy Robinson-adjacent and launder their opinions through the ongoing performance of naivety.) The loss has to be coupled with a total inability (or a total refusal) to move on from it, and a need to see your bad treatment as proof of your own significance.

One of the disconcerting things about cancellation is that it’s deeply personal: you are the one being cancelled. But it’s also impersonal: it’s a social process, and the victim is fundamentally interchangeable. When I was quote-unquote cancelled, it obviously happened to me, and that made it a particularly unpleasant experience for me, the person it was happening to. But I’d already seen it happen to several other people (mostly women, but also some men) before that, and it felt like an error to take this as being “about” me.

For the people targeting me, I could have been almost anyone: it was about the pleasure of collective feeling in choosing a victim. It was about a sexist determination to squeeze women out of public life, and demand the highest level of purity and conformity from those within it. It was about the fact that the belief system I had criticised was particularly fragile: it was easier to attack me as an individual than it was to defend, for example, the trans activist movement’s exploitation of suicide victims for political capital.1

Scapegoating, woman-hating, doubling down on sunk costs: all those phenomena can be found in any political or social grouping. They matter (they matter a lot when you’re on the sharp end) but they don’t mean very much, and having been in receipt of them didn’t mean very much about me except that I was in the right (or wrong) place to receive them. I am proud of the work I’ve done, but all I’ve ever done is try to write what seemed true and interesting. I was just being a journalist. The Sarah of it was fairly irrelevant.

But there’s another way you can take this. You can say that it was personal to you. That you must be a particularly brave or consequential person to be victimised in this way — that your cancellation is proof that you are a meaningful individual. (Maybe you’ve always suspected as much, and this is just the evidence you were waiting for.) You can, in short, embrace martyrdom, and I do see the appeal. The belief that your sacrifice was for something is seductive.

It’s also a shortcut to a terrible way of interpreting the world. If the only principle you have to hand is that you have been maltreated, everything that reminds you of that maltreatment will be incorporated into the imaginary big bad that you see yourself fighting. This is how people get from “I was unjustly called a Nazi because I don’t think humans can be born in the wrong body” to “all accusations of Nazism are unjust” to “hey maybe the Nazis have a point”.

In the minds of those driven mad by cancellation, they have heroically withstood being traduced by the left, therefore everyone who claims to have been traduced by the left must be a hero. It’s a faulty syllogism, but it has the powerful benefit of confirming your own importance — and your enemies’ evil. There is also a joyful display of spite in it: well, if you insist on calling me a Nazi, maybe I’ll just go ahead and become one. They had no fundamental beliefs to begin with, possibly. They have simply believed was appropriate to their social standing. When their social standing changes, the beliefs can too.

The people who become the most radicalised are often the ones who are most fixated on the idea that they’re “owed” something. Either they long for the return of the status that was taken with their cancellation, or they long for a level of status that they believe has been unfairly denied them. Sometimes I’ve spoken to people in the raw throes of their own cancellation and they’ve said something like: I just want someone to say that they’re sorry.

Again, this is something I understand — something I recognise from my own experience — but it’s also something that will never happen. There is no justice, and unless you were (for example) unfairly fired and are able to take your employer to tribunal, there never will be. (Even then, you still won’t get your job back.) What happened to you was unfair, and nothing will ever make it fair. There will be no reckoning, no collective apology; no one will ever put right the wrong you suffered, so you had better learn how to live with it.

When people don’t want to take that advice, my suspicion is always that they are too committed to their victim role to retreat from it. Whatever pain they suffer is more than compensated by the sense of purpose they enjoy — and the admirers they have been able to collect. Wound-dwelling is not a pleasant existence; but you can do it for so long, you forget that any other kind of existence is possible.

I’ve seen a lot of people go mad on the internet now, and I don’t think I’ll ever stop finding it horrible. I am, for various reasons, acutely aware of the wreckage a retreat into martyrdom can cause, both to the person directly affected and to those close to them. I feel very sorry for the people it happens to. But I also don’t think it “just happens” to them. It is a choice they make. They have preferred the thin reality of the internet to imperfect, fleshy life. Few brains are robust enough to survive that choice.

Gimme, gimme more…

Still not over the Olympics, so I wrote for the Times about how Raygun should embrace the noble role of the heroic failure (rather than bitch about the exact kind of zero she scored).

For UnHerd: Phyllis Schlafly, original tradwife — as in, like the tradwives today, she used her domestic queen act to make her actual extreme levels of competence and ambition seem palatably feminine.

Since Von Dutch is back (thanks Charli), here’s an article about its invention as a brand and the Nazi who’s been tactfully written out of its history (NYT). I feel bad about my new sweatshirt :(

I watched the Netflix documentary about Lou Pearlman, boyband impressario slash ponzi scheme fraudster slash alleged sex offender. It downplays the molestation stuff a bit (maybe because the people making those allegations already contributed to earlier documentary The Boy Band Con)2 but otherwise does a decent job. However the choice to have AI footage of Pearlman “reading” his autobiography is bizarre and kinda unethical?

Alain Delon: terrible human (even if you think you’ve got got the measure of the fascism and the thuggery, there’s the disowned son to be horrified by), but good lord he was cool in movies.

Two years after I wrote critically about the circulation of Leelah Alcorn’s suicide note, I made the same point about Linkin Park singer Chester Bennington’s. Absolutely no one accused me of wishing children dead that time, because there was no associated political cause to rally for.

Is YouTube still making these original docs? It doesn’t look like it from the channel, which I guess is a small but significant sign of the end of the great content boom.

I love your stints on BAR pod, and all that you write. I just had this thought about the mindset you describe: ‘you must be a particularly brave and consequential person to be victimized in this way,’ as a plausible explanation for why someone (say, my 21 year old daughter) who’s called herself he/him for 8 years while taking no steps to modify her body (thank god) continues to bang the pronoun drum. Because it leads in 10 out of 10 cases to ‘being misunderstood,’ due to its incoherence. Making her a brave and consequential victim. Makes as much sense as any other theory! This is too long for a first time comment, sorry— and thanks. 🙏

I think a strong friendship network that doesn’t enable you has a really strong role to play as well